More and more transactions are not only being completed online but are also being paid for with virtual currency. Particularly in the case of so-called in-game goods, minors make up a significant portion of the target audience. More "lives" for another attempt to reach the next level, a rare mount or a particularly powerful weapon for the historical hero, a new virtual skin for the battle royale – all of this can be purchased with virtual currencies. Especially in so-called free-to-play games, the commercialization strategy often relies heavily on such (micro)transactions, as virtual in-game currencies are initially acquired with traditional money.

To counteract manipulation and deception in these transactions, the Consumer Protection Cooperation Network ("CPC Network") published guiding principles for merchants offering virtual game currencies for payment on March 21, 2025. The CPC Network consists of national consumer protection authorities from the European Economic Area and is coordinated by the European Commission. Through cooperation within the CPC Network, of which Germany's „Organisationseinheit VS-Verbraucherschutz und Durchsetzung” (organizational unit VS-Consumer Protection and Enforcement) forms a part, consumer protection is to be strengthen and made more uniform. While the unit was still located at the Umweltbundesamt (Federal Environment Agency) in the 20th legislative period, consumer protection will fall back under the jurisdiction of the Federal Ministry of Justice according to the recently published coalition agreement of the German conservative and social democrat parties.

On March 21, 2025, the European Commission urged a Swedish online game provider to provide the CPC Network with information about business practices that could be harmful to minors, such as direct appeals to children in advertising or limited-time offers of game currencies. This approach exemplifies the regulatory trend in the EU to specifically counteract so-called "dark patterns," i.e., user interface designs with (presumably) manipulative effects.

This article presents the new recommendations of the CPC Network regarding in-game currencies and shows how the EU's digital regulation overall targets "dark patterns."

I. Recommendations of the CPC Network

The CPC Network outlines a series of (non-exhaustive) principles in its publication, which it believes concretize the requirements of Directive 2005/29/EC on unfair commercial practices ("UCP Directive") and Directive 2011/83/EU on consumer rights ("CR Directive"):

1. Price Transparency (Art. 6(1)(d), Art. 7 UCP/Art. 6(1)(e) CR Directive)

- The price indication of virtual currencies and other in-game content should be clear and transparent. For consumers, the real value of fictional currency is often unclear. Therefore, it is necessary to clearly indicate the real price in addition to the virtual payment.

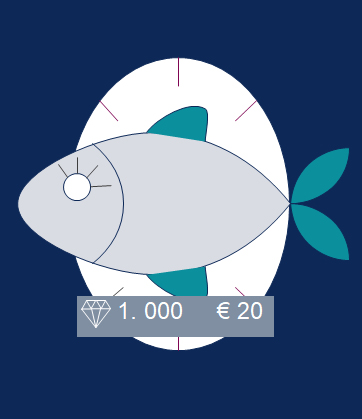

Image: Positive example for clear indication of price according to the guidelines - Practices that obscure the true costs of digital content and services also violate the principle of price transparency. The CPC Network cites the mixing of different virtual currencies as an example.

2. Prohibition of Harassment (Art. 5, 8, 9 UCP)

- Merchants must not pressure consumers into transactions, such as purchasing virtual currencies, within the game. According to the CPC Network, it is a violation to offer game currencies in packages that prevent players from limiting the purchase to the desired amount. If the desired costumes for the virtual character cost 33, 66, and 99 "cybereuros" (or similar), this virtual currency must not only be available in packages of 50, 150, and 200. The CPC Network demands the possibility for consumers to purchase self-chosen amounts of in-game currencies.

3. Pre-Contractual Information (Art. 6 CR Directive)

- Along with the offer of virtual currencies and other content, consumers must be provided with all necessary pre-contractual information. This includes the identity and contact details of the merchant, the price in real currency, the right of withdrawal, payment methods, and information on the nature of the provision. According to the CPC Network, these details must also be provided when in-game content is purchased with virtual currency.

4. Right of Withdrawal (Art. 9-16 CR Directive)

- The purchase of in-game currency entitles consumers to withdraw. Digital content can be excluded from the right of withdrawal if the buyer explicitly confirms this in advance (but not with the same "click" that triggers the purchase). However, according to the CPC Network, virtual currency is not considered digital content, so the right of withdrawal cannot be excluded. This is to apply regardless of whether the buyer pays with real money, another virtual currency, or personal data.

5. Clarity and Fairness (Art. 3(1) and (3), 5-8 UCP Directive)

- Contract clauses must be written in clear and simple language and must not disadvantage the consumer. The CPC Network cites negative examples such as clauses that grant the merchant unilateral rights to determine the value of virtual currency or the right to remove in-game content at any time.

- The CPC Network also emphasizes the protection of vulnerable groups such as children. Merchants must consider if their offer may attract minor customers, even if it is aimed at an adult audience (cf. Art. 5-8 and Point 28 of Annex I of the UCP Directive). Even groups that are not generally considered vulnerable in the analog world can be seen as vulnerable in the context of video games and microtransactions. Particularly strict requirements may apply to games whose commercialization strategy relies on a few players spending a lot of money (so-called "whale hunting").

Violations of the recommendations do not always directly result in enforcement actions. However, the document outlines cases where consumer protection authorities typically intend to take action. In Germany, the mentioned "VS-Verbraucherschutz und Durchsetzung" unit usually becomes active, but it can also commission the Bundesverband der Verbraucherzentralen und Verbraucherverbände – Verbraucherzentrale Bundesverband e.V. (Federal Association of Consumer Centers and Consumer Associations) and the Zentrale zur Bekämpfung unlauteren Wettbewerbs Frankfurt am Main e.V. (Central Office for Combating Unfair Competition) to enforce private claims. Additionally, the Bundesnetzagentur (Federal Network Agency), the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (Federal Financial Supervisory Authority), and the consumer protection authorities of the federal states can take action. They can also order the cessation of violations against consumer protection (Art. 9 CPC Regulation).

In the case of a so-called widespread infringement under Art. 3(3) CPC Regulation (§ 5c(1) UWG) or in the context of coordinated action by EU consumer protection authorities (Art. 246e § 2 EBGB, Art. 15 ff. CPC Regulation), fines of up to EUR 50,000 may be imposed (Art. 246e § 2 EBGB; § 19 UWG). For companies with annual revenues exceeding EUR 1,25 million, the maximum fine framework increases steeply to up to 4% of annual revenue (§ 19(2) UWG). If the infringement is limited to the national level of a member state, no fine may be imposed. In the online environment, however, a violation of consumer rights will regularly affect multiple countries.

Furthermore, consumer protection violations at the national level can result in claims for damages by consumers (§ 9(1) sentence 1 UWG), such as in the case of unlawful advertising targeting children (§ 3(3) in conjunction with Annex 1 No. 28 UWG).

Competitors may also assert claims for damages (§§ 3, 7 UWG). In any case, they, as well as certain associations, have the right to issue a warning to the infringing company, requesting it to cease the infringing behavior in the future and to submit a cease-and-desist declaration with a penalty clause within a deadline (§ 13(1) UWG). If this is not submitted, the claim for cessation or removal can also be enforced through litigation.

In addition to official measures, there is also the risk of private enforcement. Consumers themselves have the option to proceed collectively through a so-called injunction lawsuit and/or through consumer associations in the context of a remedial action or model declaratory action, § 1 Verbraucherrechtedurchsetzungsgesetz (Consumer Rights Enforcement Act). The latter can also directly sue for damages on behalf of consumers. Since Verbandsklage (representative lawsuits) are publicly announced in the Verbandsklageregister (representative lawsuit register), such initiatives can have significant pull and public impact.

II. Dark Patterns as an Emerging Taboo

Criticism of "dark patterns" is not new. Since at least 2022, the manipulation of user behavior through the design of user interfaces has been on the agenda of regulatory authorities.

The data protection authorities of the EU, organized in the European Data Protection Board, pointed out in their guidelines on "dark patterns" in social media platform interfaces dated March 14, 2022, that certain "dark patterns" violate the principles of transparency and data minimization laid down in the General Data Protection Regulation ("GDPR") (cf. Art. 5(1) GDPR). For example, data protection notices that can only be found through multiple clicks across different user interfaces violate the transparency requirement. Similarly, a violation occurs if pop-up windows constantly appear during the use of a service, urging the user to consent to the processing of their data and being worded in such a way that the user feels guilty if they refuse data processing. A typical negative example is working with brightly blinking or oversized buttons that draw the user's attention to the "Agree" button.

The Digital Services Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 – "DSA") also aims to curb "dark patterns." To create a safe and trustworthy online environment, the DSA imposes measures on providers of online intermediary services, particularly for moderating illegal content. Additionally, it obliges providers of online platforms not to deceive, manipulate, or otherwise restrict their users' decision-making freedom through the design of their online interfaces (Art. 25(1) DSA) and to design their service accordingly (Art. 31 DSA). This still rather abstract requirement is to be concretized by guidelines from the Commission, with the Commission already in the exploratory phase regarding guidelines for the protection of minors on online platforms. Violations of this obligation are punishable by a fine of up to EUR 100,000 under § 33(5) No. 19, (6) No. 2 lit. b) Digitale Dienste Gesetz (German Digital Services Law).

In parallel, the CPC Network, together with the European Commission, can order enforcement measures against the company for violating consumer protection law. An example of this is the European Commission's action against Whaleco Technology Limited, the company behind the online platform Temu. Even during the ongoing proceedings against Temu for alleged violations of the DSA, which the European Commission initiated on October 31, 2024, the consumer authorities of Belgium and Ireland, as well as the German Umweltbundesamt, coordinated by the European Commission within the CPC Network, instructed Temu on November 8, 2024, to adapt its practices to comply with EU consumer law.

The AI Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689) also includes provisions aimed at countering manipulative designs. Specifically, Art. 5 AI Act targets "dark patterns" by prohibiting certain uses of AI systems. For example, it is forbidden to use an AI system that employs manipulative or deceptive techniques with the aim or effect of significantly altering a person's behavior to their detriment (Art. 5(1)(a) AI Act). Even without the use of manipulative techniques, the use of AI systems with the aim or effect of such behavior modification is prohibited if it exploits the vulnerability of certain individuals or groups (Art. 5(1)(b) AI Act). This would also include an AI system used in-game that drives children, gambling addicts, or other individuals with weakened impulse control to expenditures that threaten their livelihood without relevant value.

Although a legal framework to curb "dark patterns" already exists, the Commission, based on its "Digital Fairness Fitness Check" published in October 2024, believes that consumer rights in the online environment are currently insufficiently protected. To further curb unethical business practices related to "dark patterns" and better protect vulnerable groups, the Commission has therefore set out to develop a "Digital Fairness Act." In a related "mission letter," Commission President von der Leyen specifically declared the regulation of "dark patterns," manipulative or addictive user interface design, marketing by influencers on social media, and personalized advertising as the goals of the legislative project. Even with timely public involvement, a draft of the Digital Fairness Act is unlikely to be published until 2026. Whether the Digital Fairness Act will be enacted in the form of a regulation is still open. It could also be published as a directive or as a package of measures that amends existing directives and regulations.

III. Conclusion

It remains to be seen whether the "Digital Fairness Act", in conjunction with existing regulations, will succeed in maintaining consumer trust in the online environment while preventing the abuse of manipulative techniques. Providers of online games with in-game currency should carefully review the guidelines published by the CPC Network and take them into account in the design of their online games. Special attention should be paid to the needs of children, who are more easily influenced than adults. Consumer-friendly design in the online sector can support sustainable economic success. The enemy in online games should continue to be fellow players – not the game provider.