Data processing in the cloud offers invaluable practical advantages in terms of affordability and flexibility of computing power. This is particularly true in the healthcare sector, where the required data quality often means that the data sets to be analyzed and otherwise processed are commensurately large. Clinical research, remote health care, and innovative health services all require significant computing power and data storage space.

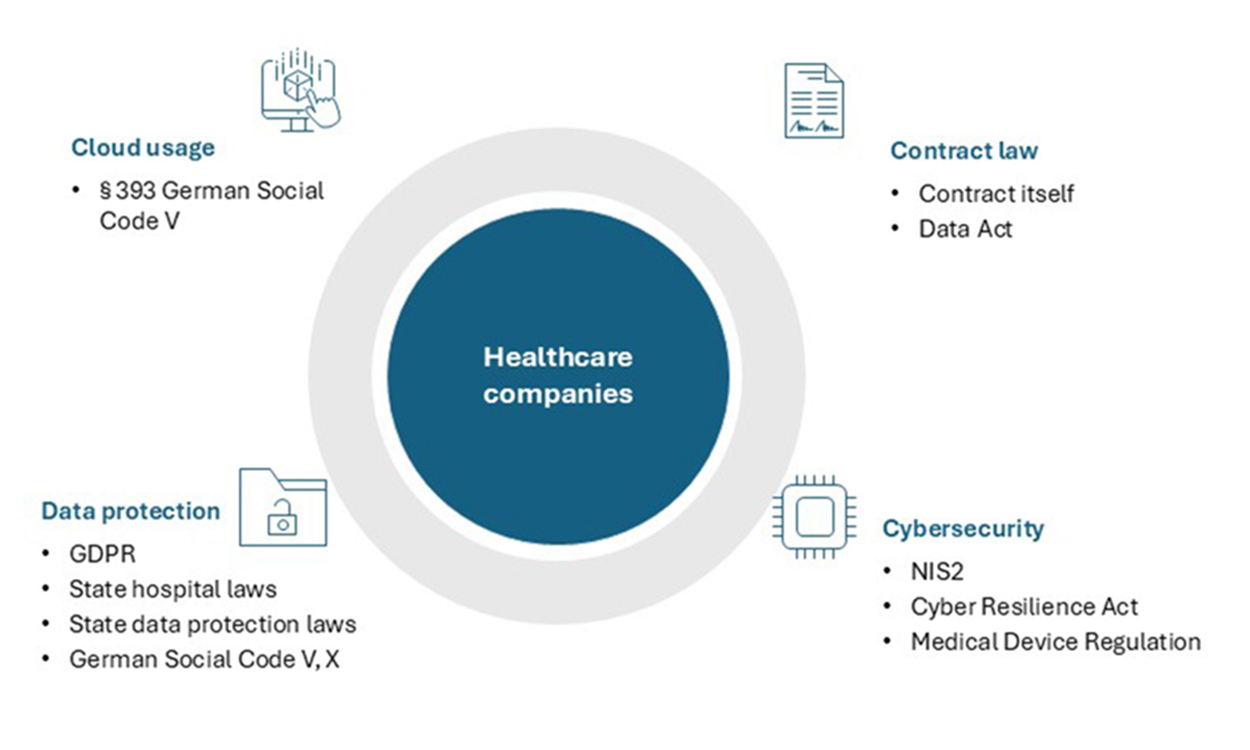

The relatively decentralized nature of the healthcare market in Europe means that individual market actors often face difficulties in operating the necessary technical equipment on its own (i.e., “on-premise”) and therefore choose to rely on third-party providers. However, the regulatory landscape governing health data in the cloud is complex and continually evolving, yielding both chances and challenges. This newsletter aims to provide an up-to-date overview of a regulatory environment that is both daunting and promising.

I. Old but gold: Data protection

Data concerning healthcare is primarily data with a high level of sensitivity. This poses challenges in regard of the processing by third parties, leading to the necessity of strict regulation that needs to be tackled by cloud computing service providers.

The regulatory framework for data protection in the healthcare sector is multifaceted, primarily governed by the General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”), the German Social Code V, and the German Social Code X. These regulations impose stringent requirements on the processing of health data, necessitating careful selection of reliable cloud service providers and the conclusion of comprehensive data processing agreements.

1. GDPR

Under the GDPR, health data is classified as a special category of personal data, meaning that its processing is only permissible under a very narrow set of circumstances (Art. 9 GDPR).

Just recently, the Court of Justice of the European Union held that even data submitted by a customer ordering non-prescription medication qualifies as health data, arguing for a broad scope of the term in light of the sensitivity of such data and the purpose of the GDPR to protect the individual data subject (Case C-21/23, Lindenapotheke) health data includes all data that can be used to draw conclusions about the health of a natural person (i.e., not necessarily the person who orders the medicine).

When outsourcing the processing of healthcare to third-party providers, healthcare companies must therefore be particularly careful to ensure that they meet the regulatory requirements.

- First and foremost, such outsourcing requires a binding agreement on commissioned data processing with the (cloud) service provider, who must also provide appropriate guarantees that the data is handled securely (Art. 28(1), (3) GDPR).

- Verification that the service provider has implemented the appropriate technical and organizational measures to safeguard the data, including data encryption, access controls, and regular security audits, is often difficult for healthcare companies. As they are requiring assistance with their data processing in the first place, they often lack the expertise and staff resources to fully audit their providers – however, reliable providers should generally be able to provide certifications such as ISO 27001, SOC Type 1 and 2 and, in Germany, the so-called BSI-Grundschutz. For cloud computing service providers, the so-called C5 attestation can also be very useful.

- For healthcare companies, it can be a useful strategy to go “directly to the source”, i.e. the infrastructure provider in the background, instead of engaging one of the many “middlemen” who all use the same sub-contractor. This way, companies can both simplify their contractual set-up, reduce costs and limit the amount of “sub-processors”, the engagement of which they must assess and approve under Art. 28(2), (4) GDPR. For healthcare companies that rely on a number of third-party providers, it can make sense to create their own template agreement. However, it should also be noted that the larger service providers with their own legal and compliance departments typically only use their own templates.

Finally, healthcare providers need to make sure that there are sufficient safeguards in place to ensure that the region where “their” health data is processed provides an adequate level of data protection. Outside of the EU, this is the case for companies like Canada, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland and the UK, all of which have been recognized by the EU Commission as providing appropriate protection. Since the adoption of the so-called EU-US Data Privacy Framework, even companies in the US may enjoy this special status, provided they are certified under the framework, which many large providers are. Only where this is not the case may it be necessary to conclude additional agreements (so-called standard contractual clauses).

2. German Social Code

The German social security legislation further complicates the regulatory landscape by imposing additional data protection requirements. For instance, the newly introduced Section 393 German Social Code V sets forth explicit requirements for healthcare service providers and statutory health insurers when they process social data using cloud computing services. In particular, under this provision, a specific type of certificate only available from the German Office for Information Security (Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik), the C5 attestation, is required to show that the necessary technical and organizational data security measures have been taken.

In addition, Section 393 German Social Code V imposes stricter data localization requirements than under the GDPR, namely that if the data is processed in a third country, the processor must have a branch in Germany – a feature that not all cloud computing providers offer, but which can sometimes be met if the service is provided by so-called “system integrators” which function as the intermediary to a non-EU hyperscaler.

Finally, Section 80 (1) German Social Code X stipulates the additional requirement that the competent authority must be notified prior to commissioned processing. While this requirement adds complexity to procurement processes, it can be managed well if anticipated from the outset.

3. State Hospital/Data Protection Laws

In some federal states, the regional hospital laws provide for additional requirements. In particular, these hospital laws often refer to patient data, an even broader term than health data as referred to in the GDPR.

4. German Criminal Code

Not only can a breach of data protection law lead to administrative sanctions and damage claims, it can also under certain circumstances qualify as a criminal offence. The disclosure of secrets or individual details about personal or factual circumstances by healthcare professionals is criminalized by Section 203 German Criminal Code. However, if data is transferred to the cloud service provider only in encrypted form, i.e. without the possibility for the cloud computing provider to view it (sometimes called “bring your own key”-solution), the transfer typically does not constitute a disclosure in the sense of this provision. In addition, disclosure to third-party providers can be lawful if these are subjected to sufficiently strict confidentiality obligations (Section 203(3), (4) German Criminal Code).

Seen in total, it becomes obvious that these requirements demand that healthcare providers only engage reliable third-part providers that provide both a sufficiently sophisticated technical set-up as regards data security and agree to the relevant legal agreements.

II. Young and wild: Cybersecurity

In addition to existing data protection regulations, new cybersecurity requirements are on the horizon, further complicating the regulatory landscape for cloud processing in the healthcare sector.

1. NIS2 in healthcare companies

The so-called NIS2 Directive obliges all EU member states to significantly enhance their cybersecurity regime by 18 October 2024, and while many member states will miss this deadline, most will likely achieve implementation by early 2025.

Under the NIS2 implementation law, providers of health services (cf. Directive (EU) 2011/24), medical research companies (Section 2 German Medicines Act - Arzneimittelgesetz), pharma companies (vgl. C 21 NACE Rev. 2) and manufacturers of medical devices and in-vitro diagnostics (as defined in Regulation (EU) 2022/123 and Regulation (EU) 2017/745) will also face increased cybersecurity obligations, in particular the obligation to register, to train both management and employees, to report certain cybersecurity incidents (within 24 hours) and generally to take cybersecurity precautions that are adequate and effective. Only manufacturers that generate EUR 10 million or less in annual turnover or have an annual balance of EUR 10 million or less and that employ fewer than 50 people will be exempt.

2. Relevance of supply chain

Cybersecurity measures under the NIS2 regime specifically include measures not only for the company itself, but also with regard to its supply chain. Similar to the various data protection requirements mentioned above, this cybersecurity requirement will at least nudge companies towards relying on established providers with a sophisticated technical and legal set-up.

III. Conclusion and outlook

The use of cloud computing services in the healthcare sector offers significant benefits, but it also presents numerous legal challenges. Both the technological and commercial opportunities and the regulatory complexities seem to be continuously increasing.

AI, whether generative or not, and the AI Act are one such example, the Data Act and its opportunities for data access and (secondary) use are another. Cloud computing will also play a pivotal role under these trends, as the prodigious requirements of computing power for AI applications and the accessibility requirements for data generated by connected products and related service both make clear.

A third example is the European Health Data Space (“EHDS”), approved by the European Parliament in April 2024, which aims to promote better exchange and access to different types of health data across the European Union. This initiative is supposed to empower individuals to take control over their health data and facilitate the exchange of data for the provision of primary care to patients (primary use of health data) as well as establish a system for reusing health data for scientific research purposes (secondary use of health data). As such, the EHDS creates a huge demand for digital infrastructural services, such as cloud spaces for storing and processing health data and digital health record systems.

Healthcare providers will soon find it difficult to stay competitive without significant reliance on cloud computing services, making it even more important they they choose the right providers (even if they do not build their own capabilities) and comply with the pertinent legal requirements when outsourcing their data processing to them. Partnering with large, experienced cloud service providers can relieve healthcare providers of a significant part of the technical (and to some extent also the regulatory) burden but is no replacement for earnest engagement with the commercial and legal aspects of cloud computing.