Both the supply of and demand for telemedicine services are increasing exponentially. 2021 already brought crucial changes to telemedicine healthcare in Germany: the obligatory electronic patient record (elektronische Patientenakte, ePA), a growing number of prescribable digital health applications (Digitale Gesundheitsanwendungen, DiGAs), as well as video consultations for non-physician therapists such as physiotherapists and ergotherapists as well as midwives. With the entry into force of the Digital Act (Digital-Gesetz, “DigiG”) on 26 March 2024, telemedicine treatments have become a fixed part of healthcare provision. The DigiG will have a major impact on the introduction and functionality of electronic patient records, electronic prescriptions (“e-prescriptions”, E-Rezepte), digital health applications, and the range of telemedicine services on offer.

Against this background, the current legal status in Germany, including the latest amendments, is summarised below.

I. Online consultation hours as a fixed part of physicians’ work in Germany

Seldom performed in Germany prior to 2018, online consultation hours have since become a fixed part of the healthcare offered by physicians. Several providers have now established certified portals enabling physicians to conduct consultations with patients insured under either statutory health insurance (SHI) or private schemes.

- Since 2018, the (Model) Professional Code for Physicians in Germany ((Muster-)Berufsordnung für die in Deutschland tätigen Ärztinnen und Ärzte, “MBO-Ä”) has allowed patients to be treated remotely only, without prior initial contact in person between physician and patient, though subject to certain conditions. Such treatment must be medically justifiable, physicians must continue to take due care, and the patient must be informed of how consultation and treatment only via communication media differ from conventional approaches (section 7(4) MBO-Ä). Physicians may provide both private and SHI-accredited consultation hours online across Germany.

- All of Germany’s medical associations have now implemented the provision from the MBO-Ä, with the Brandenburg State Medical Association being the last to adapt its former provision on remote treatment to reflect the MBO-Ä with effect as of 14 May 2024.

Since 1 April 2019, consultations conducted online have also been billable to the SHI funds.

Currently, SHI-accredited physicians primarily bill their basic charge and flat charge per patient for video consultations. Depending on whether the relevant prerequisites are met, surcharges and further billable services may also be applied (e.g. for specialist primary care or fulfilling the primary physician’s mandate to provide healthcare).

Video case conferences, where physicians with different specialities discuss a case, have also been widely facilitated in SHI-accredited healthcare (section 87(2a), sentences 14 to 15 Social Security Code, Book V (Sozialgesetzbuch, Fünftes Buch, “SGB V”)). On 1 October 2020, the Committee for Rating SHI-Accredited Physicians’ Services (Bewertungsausschuss) decided to include and remunerate video case conferences in all medical areas in the Uniform Evaluation Scale (EBM), with patients attending such conferences in some cases.

- The entry into force of the DigiG has led to another change: As of 26 March 2024, it is now possible to perform SHI-accredited work in the form of video consultations outside of the practice’s registered office (section 24(8) Ordinance on the Accreditation of SHI-Physicians (Zulassungsverordnung für Vertragsärzte, “Ärzte-ZV”)). Accordingly, it is now permissible for physicians to provide their services from home. This increased flexibility is nonetheless subject to compliance with the existing duties to offer minimum consultation hours and open consultation hours at the SHI-registered office (section 19a(1), sentences 2 and 3 Ärzte-ZV).

- Since 7 October 2020, it has also been possible for patients to obtain a doctor’s certificate via video consultations. Where certificates of incapacity to work are then issued, SHI-accredited physicians have had to send such certificates to the SHI funds digitally since 1 October 2021. Employers have been integrated into the electronic procedure since 1 July 2022. Upon receiving the data on the incapacity to work, the SHI funds must generate a notification for retrieval by the employer, which must comply with certain technical re-quirements in order to retrieve this (section 109(1) SGB IV (Sozialgesetzbuch, Viertes Buch)).

- Private health insurance companies frequently conclude cooperation agreements with individual telemedicine portals, enabling the persons insured by them to consult physicians free of charge by means of these portals (without requiring them to make later claims for reimbursement of costs).

II. Focus remains on-site healthcare by SHI-accredited physicians in independent practice

- Like out-patient healthcare on site, rendering telemedicine services within the SHI system depends on SHI accreditation (section 95 SGB V). So for investors or telemedicine service providers who want to provide more than merely software, an online platform or corresponding technical services, the only remaining option will usually be to acquire a legal entity entitled to establish an ambulatory healthcare centre, for example a certified hospital included in the Regional Hospital Plan (Plankrankenhaus).

Even following these changes, including the Digital Healthcare and Nursing Care Modernisation Act (Digitale-Versorgung-und-Pflege-Modernisierungs-Gesetz) – which entered into force on 9 June 2021 – and the DigiG – which entered into force on 26 March 2024 –, telemedicine remains a secondary activity for SHI-accredited physicians.

However, the statutory restriction of online consultation hours to 30%, which had been applicable in the SHI system since 1 April 2022, was eliminated on 26 March 2024. Section 87(2a), sentence 30 SGB V, which had previously imposed this restriction, was repealed by the DigiG.

The aim is to establish telemedicine as a fixed part of healthcare provision. Once the German medical profession’s self-governing bodies have implemented the DigiG, SHI-accredited physicians will therefore have greater flexibility and scope in offering video consultations. This corresponds to the legal situation that already applied during the coronavirus pandemic, when unrestricted online consultation hours were enabled after the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, “KBV”) and the SHI funds lifted the relevant restrictions. However, if the only contact is via video consultation and the patient does not visit the practice in person during the quarter concerned, the SHI fund will apply a percentage deduction – specific to the relevant specialisation – of up to 30% on the respective flat charge/surcharge.

SHI-accredited physicians must additionally continue to fulfil their existing duties to offer minimum consultation hours and open consultation hours at the SHI-registered office (section 24(8) Ärzte-ZV). Purely online SHI-accredited practices do not exist at the current time, and consequently will not exist in the foreseeable future either. The SHI-accredited physician’s work will continue to be centred around patient care on site, in the physician’s practice.

III. Minimum technical requirements for telemedicine products

Entry into the new market of telemedicine as a video consultation provider is also contingent on compliance with specific technical requirements:

- Video service providers who facilitate video consultations as well as communication service providers who transmit data for physicians to confer on findings must be certified in accordance with the requirements of Annex 31a and 31b Federal Framework Contract pertaining to Physicians (Bundesmantelvertrag-Ärzte). Among other things, they must comply with data protection and data security requirements.

- Compliance with the requirements imposed by the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds (GKV-Spitzenverband) and the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians is verified by independent certifying bodies which check the relevant pieces of proof that must be provided. Currently, there are 43 certified video service providers (as of 20 September 2024).

IV. How likely is competition between the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians and private telemedicine portals?

- For SHI patients, the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians is to set up a new electronic system for assigning online consultation hours with SHI-accredited physicians, as provided by section 370a(1) SGB V. The DigiG has introduced deadlines for this purpose: 30 June 2024 for the referral of telemedicine services and 30 June 2025 for the referral of treatment appointments. Both video consultations and treatment appointments can now be booked online via the 116117 patient service, for which the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians is responsible (116117.de - Der Patientenservice: die Leistungen | 116117.de).

- The private portals established in the market to date must pay a fee to receive the information provided in the electronic portal of the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians (section 370a(4), sentence 1 SGB V). After the Federal Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, “BMG”) transferred the power to issue ordinances to the Federal Association on 24 June 2024, the latter has now issued rules of procedure for the use of the electronic system for referral of telemedicine services by users of the interface.

- SHI-accredited physicians may object to the Federal Association transmitting data to third parties (section 370a(2), sentence 3 SGB V). As far as we currently know, they need not pay a fee for offering their telemedicine consultation hours on the Federal Association’s new portal.

- Germany’s federal government itself is active in digital health information. On 1 September 2020, the national health portal https://gesund.bund.de/en was set up. The portal provides information on health and nursing care, is worded in easily understandable language, is available to people with disabilities, and can be accessed via both the internet and the telematics infrastructure (section 395(1) SGB V).

V. Public advertising of telemedicine treatment

In general, there is a ban in Germany on advertising for remote treatment (section 9, sentence 1 Health Products and Services Advertising Act (Heilmittelwerbegesetz, “HWG”)). Telemedicine treatment is exempted from this, however, where generally recognised professional standards do not dictate that a physician and patient meet in person (section 9, sentence 2 HWG). Higher regional courts initially interpreted this new provision unnecessarily strictly (see for example Munich Higher Regional Court, judgment of 9 July 2020 – 6 U 5180/19; Hamburg Higher Regional Court, judgment of 5 November 2020 – 5 U 175/19).

In its judgment of 9 December 2021 (I ZR 146/20), the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) defined the criteria for “generally recognised professional standards”, thus setting Germany’s first standard for whether it is permissible to advertise remote treatment – which includes video consultations – in accordance with the requirements of section 9, sentence 2 HWG.

- For section 9, sentence 2 HWG to be applied in a legally sound and consistent way, the Federal Court of Justice ruled, interpretation of the “generally recognised professional standards” must draw on the identical term in section 630a(2) Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, “BGB”) as well as the principles developed with regard to this term and a physician’s duties under their contract with the patient for medical treatment (Behandlungsvertrag). The Federal Court of Justice took the view that drawing on section 630a(2) BGB also facilitates recourse to extensive case law when interpreting the term. This, the Court held, would enable the requirements of section 9, sentence 2 HWG to be applied in a consistent and legally sound way.

By contrast, the Court continued, section 9 HWG did not depend on whether the advertised remote treatment was permissible under Germany’s laws governing physicians as a profession.

The Federal Court of Justice rejected the provisions of the laws governing physicians as a profession as a basis for determining what constitutes “generally recognised professional standards”. Legislators, the Court held, had intended to set an abstract and general standard for determining the permissibility of advertising remote treatment. The Court noted that the decisive rule in section 7(4) MBO-Ä (new version) did not offer this abstract and general standard, however, but merely instructed the treating person with reference to a specific case. A further reason why the MBO-Ä was unsuited to a standardised interpretation of section 9 HWG across Germany was that the country’s various federal states did not (at the time of the ruling) implement the MBO-Ä in a standard way.

The Federal Court of Justice stressed that remote-only consultation had only recently become permissible and had been limited to individual cases. Only in a few cases, therefore, did remote treatment guidelines exist. But the Court also pointed out that legislators wished to further develop telemedicine opportunities, and left the impression that as long as professional standards were complied with, it would not oppose such developments.

VI. Giving demand for telemedicine services a booster

Introducing video consultation hours, which are no longer restricted by law, enables physicians to render telemedicine services from home and be remunerated for them. As part of the digitalisation of the German healthcare system, there are also a number of further projects to improve both information for physicians as well as prescribable treatment from the patient’s perspective. Closer networking between physician and patient enables a wider range of services to be offered than in the past. The following measures are noteworthy:

The electronic patient record (ePA)

- The electronic patient record constitutes a core element of digital networked healthcare and the telematics infrastructure. Since 1 January 2021, SHI funds have been obliged to offer their members the electronic patient record. Since 1 July 2021, all physicians and psychotherapists have been obliged to have the necessary equipment to transmit data centrally to the electronic patient record via the telematics infrastructure. Digital patient data are to be collected at one central point.

- However, the DigiG is bringing about a shift in direction aimed at facilitating the nationwide integration of the electronic patient record into healthcare. When the new section 344(1) SGB V comes into force on 15 January 2025, the current model based on patient consent will be replaced by an opt-out procedure. Accordingly, SHI funds will provide their members with an electronic patient record unless they object within six weeks of being informed.

- The DigiG has also introduced an opt-out solution when it comes to using electronic patient record data in research. According to section 363(1) SGB V, patients must now object to their data being made accessible instead of releasing it for research purposes.

- It is primarily medical information that is stored in the electronic patient record, but it is also possible to enter vaccination data, certificates of incapacity to work and data on the patient’s nursing care.

- To strengthen cross-border patient safety, section 219d(6) SGB V also provides for the establishment of a national e-health contact point. This will enable patients to provide physicians in other EU countries with their health data, securely and in translation. However, the DigiG scrapped the deadline for the launch of the contact point as previously provided for in section 219d(7), sentence 1 SGB V, namely by 1 July 2023 at the latest, in favour of the BMG setting a date for the launch without specifying this by law.

Introduction of e-prescription across Germany

- The e-prescription was already introduced in 2022. But its obligatory use across Germany failed previously on account of the e-prescription’s technical requirements and due to data protection concerns. Since 1 January 2024, the e-prescription has become the binding standard in pharmaceutical supply.

- The obligation to use e-prescriptions does not apply to persons who are privately insured. Since 2020, however, Germany’s Association of Private Health Insurers (PKV-Verband) has been a shareholder in gematik GmbH. Together with SHI players, the Association has been working to introduce a unified digital infrastructure for the healthcare system that links to the telematics infrastructure, thus providing patients and healthcare providers with the electronic patient record and e-prescriptions. Currently, a prerequisite for using the e-prescription is that both private health insurance companies and physicians’ practices support the e-prescription for persons who are privately insured.

Physicians issue an e-prescription digitally, signing it electronically with their health professional card. It is then stored and encrypted in the telematics infrastructure, where pharmacies can access it later. On the technical side, practices need an electronic health professional card, a link to the telematics infrastructure with a corresponding connector, and a practice management system that meets e-prescription requirements. Patients receive an access code (known as an e-prescription token) that they then give the pharmacy for the prescription to be filled. Pharmacies are obliged to fill e-prescriptions. There are various technical ways of sending the token to the patients and of having the prescription filled by the pharmacy:

The e-prescription app is available as a digital solution.

The token can also be printed out on paper – as before – and given to the pharmacy where it can then be scanned.

Since 1 July 2023 it has also been possible to have the e-prescription filled using the electronic health card, which needs to be inserted into a corresponding reader at the pharmacy.

A new option became available on 1 January 2024: All private health insurance companies and SHI funds may now include a function in their electronic patient record apps enabling e-prescriptions to be received and filled.

- Based on the DigiG, the e-prescription has now been developed further and will be integrated into the electronic patient record. This integration goes beyond merely showing an e-prescription on the app’s user interface. Unless the patient objects, further data will be sent to the electronic patient record, including the drugs dispensed, their batch number, and their dosage (“dispenser information”). So here as well, legislators have gone for an opt-out procedure that reverses the previous concept based on patient consent.

- Data transfer will form one of the pillars of a digitally supported medication process. Together with further information on allergies, intolerances, pregnancies etc., the data are made available to practices (unless the patient objects) and taken into account when prescribing drugs. For effective therapy, the interplay of e-prescription and electronic patient record promises added value in avoiding double prescriptions and improving drug safety, as physicians can better judge interactions with drugs already prescribed or with existing conditions. But that is not all. Germany’s healthcare telematics body, gematik, has been given new powers and taken on new tasks in shaping the e-prescription and developing the electronic patient record.

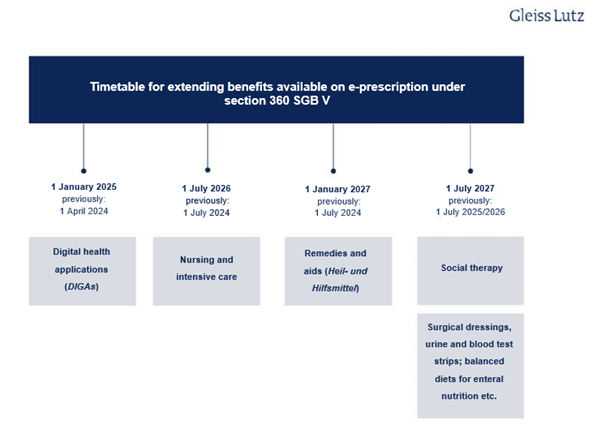

- E-prescriptions have only covered prescription drugs to date, but it is likely that they will cover all medicinal products in future. This means that the scope of the e-prescription is to be gradually expanded. Section 360 SGB V is the main statutory provision on e-prescriptions and sets deadlines for this expansion. However, due to the delay in the mandatory introduction of the e-prescription, these deadlines have been adjusted once again under the DigiG. The following overview shows the schedule for extending e-prescriptions to other benefits:

Digital health apps and telemedicine

Since Autumn 2020, digital health apps have been available under statutory health insurance as a new benefit package. The introduction of the Digital Healthcare Act (Digitale-Versorgungs-Gesetz) in 2019 laid the groundwork for the integration of these apps into standard care in Germany. An innovative industry of digital medical device developers has since emerged, with 55 apps currently provisionally or permanently listed in the official digital health applications directory of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, “BfArM”). Nine applications (provisionally) authorised as digital health apps have been removed from the list either at the request of the developer or because no positive healthcare objective could be demonstrated. The DigiG now aims to ensure that digital health apps play an even greater role in healthcare in the future.

- Before the DigiG came into force, only class I or IIa medical devices whose main function is based on digital technologies could be prescribed as digital health apps. The DigiG has extended the statutory entitlement to include apps falling under higher risk classes, namely those in risk class IIb.. This means that it will in future be possible to use digital health apps in more complex therapeutic processes as well, for remote patient monitoring for example. This opens up new opportunities for digital health app developers. Approval of digital health apps in such risk classes logically requires proof of direct medical benefit (“medizinischer Nutzen”) to the patient (such as an improvement in the state of health), and not just proof of a structural or procedural improvement in medical care that has a positive effect for the patient (“positiver Versorgungseffekt”). The DigiG also makes it clear that companion apps do not constitute digital health apps: Approval will not be granted for apps that are used only to manage therapeutic products or are (permanently) linked to very specific medical aids or medicinal products.

- Before they become prescribable in statutory health insurance, digital health apps must be included in the directory of digital health applications by the BfArM pursuant to section 139e SGB V. The areas of application of the digital health apps listed therein range from treating depression to diabetes and multiple sclerosis through to migraines. According to the report on digital health apps from the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds, around 209,000 such apps were prescribed between 1 October 2022 and 30 September 2023.

- Even before the DigiG came into force, SHI patients had a right to be provided with digital health apps. These can be prescribed by physicians and psychotherapists, and are reimbursed by the SHI fund. The requested digital health app may also be received without a physician’s prescription if the SHI fund’s statutes provide for this. Aside from in a number of tightly restricted cases, SHI funds must under the DigiG now ensure that digital health apps are, as a rule, available for use by patients within two working days of receipt of the prescription. There is no requirement for SHI approval, nor may SHI funds create de facto approval requirements, as such requirements would jeopardise prompt provision of care.

- The DigiG has also changed the way digital health apps are priced, with performance-based criteria playing a greater role in future. Section 134(1), sentence 3 SGB V stipulates that as from 1 January 2026, agreements must specify that performance-based price components are to comprise at least 20 percent of the remuneration amount. Sentence 8 requires the contracting parties for apps with an existing price agreement to set a corresponding remuneration amount by 1 January 2026. Exactly how prices will be structured in future remains an open question.

- The existing ban on referrals and agreements has been expanded by the DigiG: Developers of digital health apps are not permitted to enter into legal transactions or agreements with medicinal product or medical aid manufacturers that are likely to restrict a patient’s freedom to choose specific products or aids (section 33(5a) SGB V). The Federal Government sees this as a way of preventing lock-in effects. It is therefore unlawful to design digital health apps tailored to accompany treatment involving only one particular medicinal product or medical aid.

- Following the introduction of the DigiG, digital health app developers must in some cases allow patients to borrow the technical equipment required to use their apps. By making it possible to borrow expensive accompanying hardware, the Federal Government hopes to reduce costs and increase sustainability. However, it is not yet clear in which cases this will apply.

- The DigiG also treats digital health apps the same as any other remedies and aids offered to pregnant women and new mothers, which means that women now have the right to use relevant digital health apps both during and after pregnancy (section 24e, sentence 1 SGB V).

- Under the DigiG, patients have, subject to certain prerequisites, been given the freedom to choose what level of authentication is required for access to a digital health app and may even opt for less stringent access requirements.

- The performance of all digital health apps listed in the directory must now be assessed and the results reported to the BfArM on an ongoing basis. The results are also to be published in the directory from 1 January 2026 onwards. As already mentioned, part of a digital health app developer’s remuneration will in future depend on these results.

Opportunities to invest in digital health

- Public healthcare entities also have the opportunity to invest in digital health. Such entities include SHI funds, regional associations of SHI-accredited physicians, the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Physicians and the Federal Association of SHI-Accredited Dentists (Kassenzahnärztliche Bundesvereinigung). Pursuant to section 68a et seq. SGB V, these are entitled to promote digital innovations by assuming some or all of the costs. Digital innovations include telemedicine/networked healthcare and digital medical devices.

- SHI funds may also support or commission development by external providers. Now that the DigiG has come into force, SHI funds may invest up to 10% – instead of the previous 2% – of their financial reserves as venture capital for developing digital innovations (section 263a SGB V).

- In the development and shaping of digital healthcare, this gives SHI funds and regional associations of SHI-accredited physicians considerably more scope for cooperation with both established providers and start-ups in telemedicine services and digital medical devices.

VII. Breakout moment for telemedicine

The foundations for the – long overdue – expansion of telemedicine structures in Germany have been laid since 2018, with key changes being made in 2021. And with its introduction in March 2024, the DigiG has further improved the overall framework for both patients and telemedicine providers. Previous statutory restrictions on the percentage of video consultations have been lifted, giving – once the German medical profession’s self-governing bodies have implemented the DigiG – SHI-accredited physicians greater flexibility and scope in offering such consultations, especially combined with the now permitted option of working from home. The ongoing developments in the area of e-prescriptions are simplifying how prescriptions are issued, sent and filled in everyday practice. Online pharmacies and pharmacy platforms are also likely to benefit, as will logistics service providers that offer prompt delivery to patients directly on pharmacies’ behalf.

All things considered, telemedicine’s share in healthcare in Germany is therefore likely to continue rising rapidly over the next few years.